All Holocaust survivors’ stories are extraordinary and precious because of the extremely unlikely odds of outwitting Hitler and escaping the Nazis’ meticulous and murderous rampages. My parents’ wartime tales are extraordinary for those reasons, too, but Family Treasures Lost and Found: A Memoir differs on several counts. First, my parents were not in concentration camps. Second, their strategic trajectories as they were hounded across Europe by exterminationist anti-Semites were highly unusual.

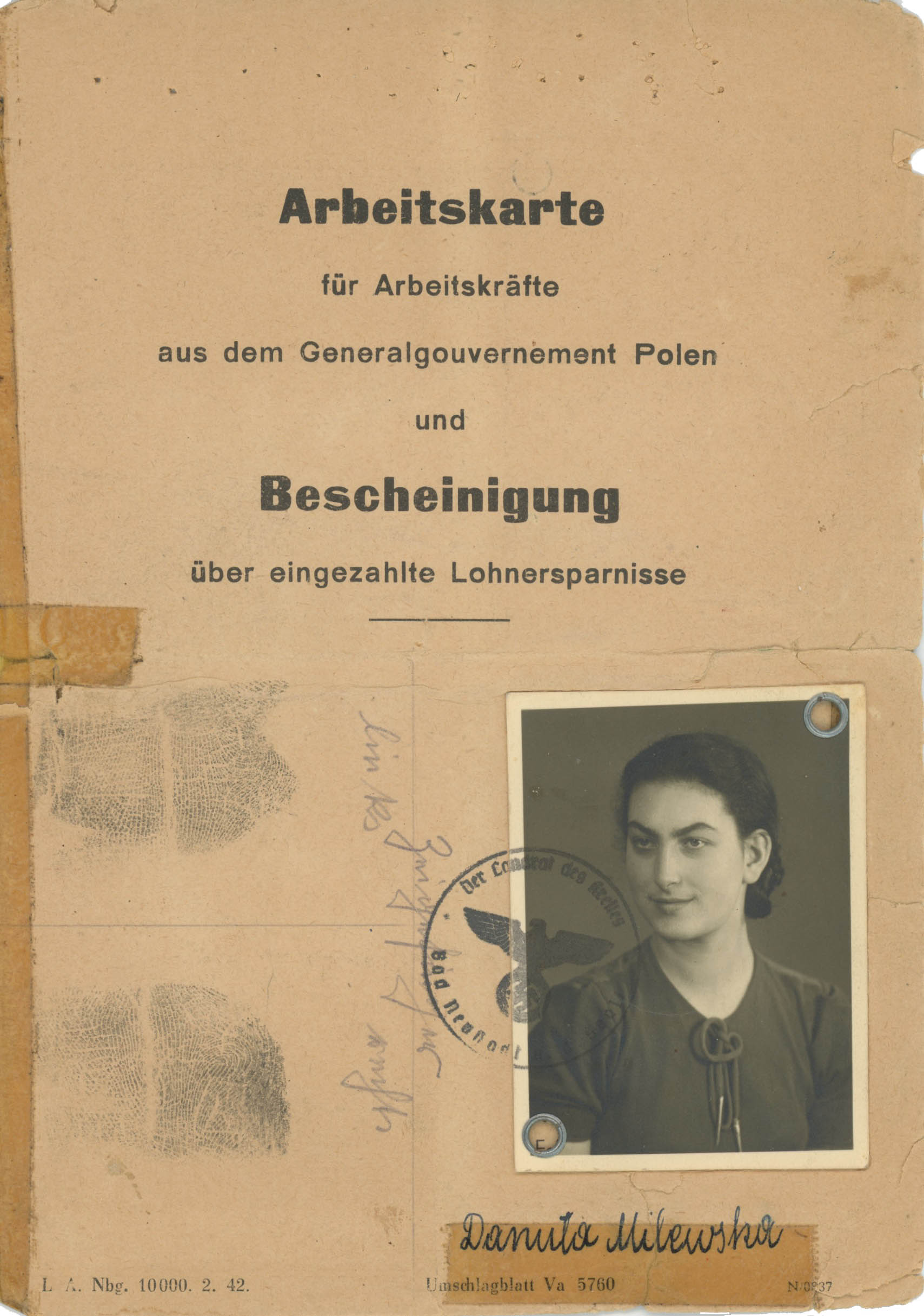

When World War II began, my mother was a sheltered fourteen-year-old living in Kraków. She and her parents fled east by train three days after the Germans invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. After zigzagging across Galicia (southern Poland), they ended up in Lwów, Poland, now Lviv, Ukraine. In the fall of 1941, she convinced her parents that they would not survive without false papers enabling them to pretend that they were Catholic Poles. She came of age sustaining this ruse and working as a slave laborer in Germany. My mother told my sisters and me about her survival, but only in snippets. She was selective in what she shared, and imparted different morsels to each of us according to what she thought each daughter could absorb.

I knew my mother’s war story was unique in many ways. Very few Jews survived with false papers posing as Polish Catholics, as she had. Fewer still had made it thanks to that ruse and by volunteering to work as a slave laborer in Germany. She literally hid in plain sight in the belly of the Teutonic beast.

My Mother's Work Card and the Name of her Alias

When I became a journalist in the 1980s, I tried many times to interview my mother. I would arrive at her home with my tape recorder, but she always demurred. “Oh come on, let’s just talk and enjoy our tea,” she would say. “Tell me how you are. What are you working on?”

In 1987, I urged my mother to record her testimony for the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University. My mom overcame her hesitation and reluctance, gathered a few documents and photographs the night before, and recorded her oral history. She faced her two interviewers with characteristic forthrightness and irony, occasionally sidestepping questions that were too painful. She did not want to detail the abuse she suffered at the mercy of her “employers,” who overworked and starved her and denied her medical care. After the interview, she told me, “Maybe someday you’ll do something with it.” I had made a request of my mother and she in turn had given me an assignment.

One day in the early 2000s, I forced myself into reporter mode and sat on the couch in front of our VCR to transcribe her oral history. At first, I had trouble watching the tape. Ill at ease, stressed, and formal, my mother hardly resembled the vivacious, charismatic, and sociable woman I admired. I felt guilty that I had imposed upon her, even though she did not fault me. It took a long time to slog through my mother’s testimony because her one-and-a-half-hour interview was filled with the names of Polish towns and cities I could not spell. I cut and pasted paragraphs of the transcript to get the chronology straight. Then I created a timeline and marked the towns and cities along my mother’s long path to liberation through Poland, Ukraine, and Germany.

Delving into my father’s past proved to be much harder. Four decades earlier—when I was fifteen—my father died unexpectedly at age fifty-seven. I remained hesitant and conflicted about delving into his past; I had been an obedient, dutiful daughter and had respected his privacy. But to better understand and memorialize my enigmatic father, I would have to defy him and uncover what he had not wanted me to know.

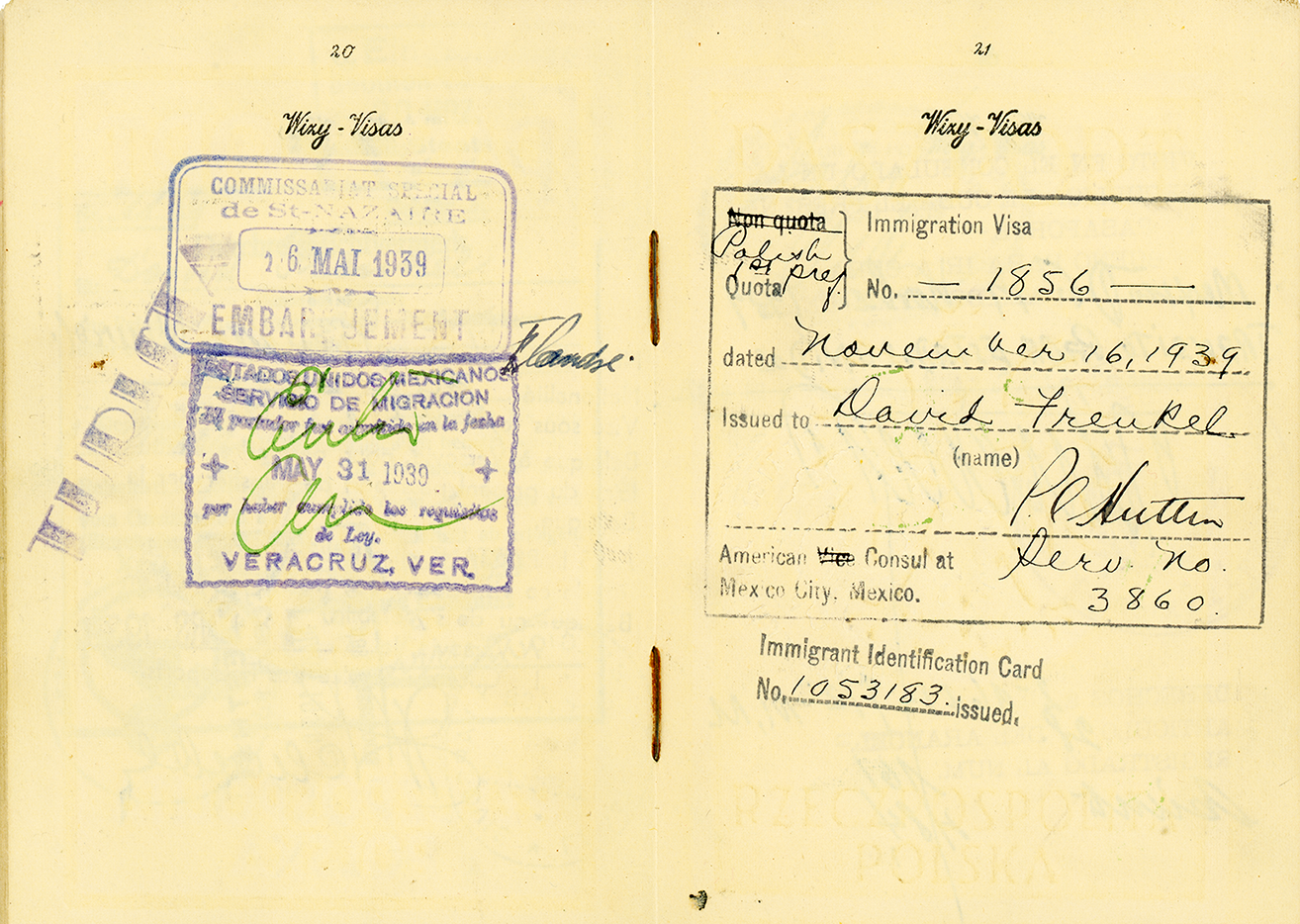

All I knew of my father’s early life was that he was born in Lwów. And that he received his medical degree from the renowned University of Vienna Medical School, but I did not know when.

Somehow my dad arrived in New York via Mexico before World War II. He finished his medical training in Brooklyn and then served in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. He refused to discuss his pre-war life and refugee experiences with my two sisters and me. The little I knew I learned from my mother and my father’s older brother. Shortly after my father died, my sisters and I learned that he had been married before he met our mother, that his first wife was the daughter of the owners of the famous dairy restaurant Ratner’s, and that she was connected to the underworld of the Lower East Side. My father and his first wife divorced when he returned from serving in the U.S. Army.

My Father's 1939 Polish Passport Showing his Arrival in Mexico

As far as I know, three of my grandparents and my father’s younger brother were never buried where they were murdered—in Nazi-occupied Lwów. There are no gravesites, no headstones. Not having been buried, my relatives’ spirits float, dispersed in the air. There is wisdom in the Jewish tradition of sitting shiva and observing a period of mourning. Without it, I wondered how my parents could have experienced even a particle of resolution.

And so I love Lwów and I loathe Lwów. Birthplace of my father, killing grounds of my three grandparents, my uncle, his wife, and tens of thousands of other Jews.

As a witness of surviving witnesses—daughter of a refugee and a displaced slave laborer; granddaughter of a survivor; great-granddaughter of two refugees; grand-niece of two refugees; and as a descendent of those who perished: granddaughter of three murder victims; niece of a murdered uncle and of numerous great-aunts; great-uncles, and cousins—and in response to my mother’s express wish, I felt obligated to research and recount both my parents’ and paternal grandfather’s wartime stories. These narratives recount the few, very unusual escapes from fascist genocide—and the fates of the vanquished eighty years ago.

In the spirit of the great Jewish sage Hillel the Elder, I asked myself: If I do not seek answers now, then when? It was 2014 and I embarked upon a seven-year fact-finding quest so that I could describe how far my parents went emotionally, physically, and morally to save themselves during the Nazi onslaught. Discoveries large and small enriched my understanding of what my parents and other relatives endured. They wanted new lives. They wanted to look to the future and not ruminate about the past and their losses, because the dead would have wanted it that way.

I disclose the details because I want the world to understand what happened to them in a way that’s real and relatable. Only then can such trauma be prevented from happening to others. My parents’ stories are important not just because they were my parents, but because—in contrast to those who survived the concentration camps—the trauma and loss experienced by displaced Jews and refugees remain largely untold. The same is true of their courage, cunning, and resilience. I did not anticipate that my parents’ stories would become relevant again when the plights of 65 million refugees worldwide were reported in 2016. I was, however, acutely alert to the rise of authoritarianism here and abroad. With the worldwide refugee crisis having swelled to 123 million as of 2023, according to the United Nations High Command for Refugees, my parents’ and grandfather’s stories take on new relevance. Family Treasures Lost and Found shows that life and freedom are worth the struggle, and that they are precious and to be cherished.

In a sense, digging up facts and writing about my parents’ stories is my response, my resistance, to those who want to rewrite history by claiming the Holocaust never happened, or insist that not that many people died, and that the Jews should just get over it. Before my quest, all I could do was retort with rhetorical questions: If that is so, then what happened to three of my grandparents? What were the fates of my Uncle Milek and his bride? Where are their graves?

But there are truths. There are facts. And I found them. I scoured the Internet, plumbed real-world archives, and retraced the steps of my parents, sole surviving grandfather, and other family members when I went to Europe in 2016. I visited Vienna, Kraków, Tarnów, and Lviv with the goal of leaving “no stone unturned,” as my mother used to say. I needed to honor my relatives by learning more about them. When details eluded me, I filled in the blanks with conjecture, trying out scenarios based on what I already knew of my relatives’ personalities and predilections.

With each discovery, I was rewarded with the most unexpected recompense: a deep sense of connection to the lost.